1914, the Christmas Truce Football Match, poetry now and then

The Christmas Truce Football match of 1914 would go down in history to become one of the most iconic events in terms of the sport that took part in wartime history. The 1914 Christmas truce period, was one of the finest recorded instances of gallantry during wartime, maybe not as comprehended by the Army Commanders as expected by those who played a part in it. The first world war had just begun, and it was expected to end soon, however, it took about four years to its Armistice and roughly around seventeen million lives of both military and civilians and about twenty million wounded.

The western front in Europe, the heart of the hottest military and political conflict of the time would be home to an emblematic moment in history. As history tells (there is not real evidence of this), Pope Benedict XV, earlier in December 1914, had suggested a short break from the war owning to Christmas, which was never sanctioned by any of the warring countries nor outspoken by any of the battalions on the field.

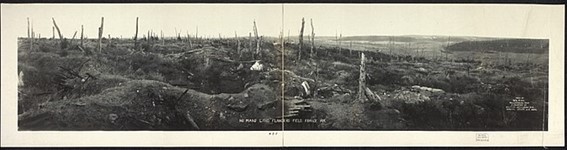

Controversially, what went on in some fronts of the war, was that on the time of Christmas of 1914, it was possible to hear carols being sung in both British and German trenches. There was then a warm Christmas spirit in the making on both sides of the no-man’s land[1]. It was never proven it happened because of the Pope’s request or just due to the fact that they were all young soldiers who did not know exactly why they were fighting each other and decided to take some time off.

Roshan Machayya, in his article, “Poetry and the Christmas Truce of 1914” from 2019, shows some pictures of where today lays a Cross that symbolizes the truce, where it is possible to see what used to be the “No man’s land” territory.

Most history books would tell us that for the duration of the truce, British and German troops would go on to sing carols, exchange gifts, show pictures of their families and tell stories to each other. It was also a moment of trying to understand why they were there, as both troops took that occasion to pick up the corpse of their fallen comrades from the no-man’s land. It is paramount to point out that most soldiers from both troops were low ranked, as their superiors would not join them down the trenches.

Machayya brings another picture that depicts this famous encounter on “No man’s land” territory.

A football match between both camps would go on to be documented. This Christmas spirit must always remind us of what war really is: never a poor person’s fight. No real evidence of a real football match can be found, however, what is more likely to be accepted is that one of the sides had a ball or balls and both sides started kicking and passing the ball to each other in a playful way.

It doesn’t matter if it was only a kick about. The fact the men used football to break down barriers of language and nationality. Shows that football can and does help bring people together in a good way.

This is the most amazing moments. Men that would have rather been anywhere else. Having to fight against each other. When they would have probably been great friends under different circumstances. The fact that any of this happened was one of the most bittersweet moments in football/war history.

There were some articles and some accounts written at the time to explain what had happened, however, those articles were written based on news report and other sources, such as this one:

“There was a sort of truce arranged to-day (Christmas Day) between some of our fellows and the Germans in front them. They even arranged a football match. Since I started writing this letter a telephone message has come through to say that the Germans had won three goals to two. ” Jan. 1915 Belfast Newsletter. Nothing would surprise me, as British regt. companies themselves had organized football matches at the front & there are plenty of accounts of those. (This is an article from Century Ireland, a fortnightly online newspaper, written from the perspective of a journalist 100 years ago, based on news reports of the time.)[2]

As there are countless tales of the match and what had happened the night before such as the one above, a century after the Christmas Truce, Sainsbury’s, a grocery store chain, partnered with the Royal British Legion to reenact this historic event[3]. It can be seen below as a moment of happiness but at the same time incomprehension about what was to come afterwards[4].

As iconic as these events would be, poetry too followed the 1914 Christmas spirit. It is important to mention here that this spirit was not depicted in the poems of the time. Most of the great writers of the early 20th century did not write about the glories and good moments the soldiers had during the 1914 Christmas truce. On the contrary, much that was written about World War One, was written by soldier poets—such as Wilfred Owen, Siegfried Sassoon, Thomas Hardy, Isaac Rosenberg, Edmund Blunden, Robert Graves, Edward Thomas, and Ivor Gurney among others. Their poetry portrayed the horrors of war through its evocative imagery of the damage it inflicted on the soldiers, the incomprehensibility of killing another person who would be your friend and not a foe given different circumstances. They also described the hard times soldiers had to go by in the trenches while their superiors were on safe grounds. Some brought to discussion the notion of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), also known as shell shock, which is a term coined in World War I by British psychologist Charles Samuel Myers to describe a mental health condition that is triggered by a terrifying event — either experiencing it or witnessing it. Owen, said of his own war poetry, “My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity.”[5] As an example of a War Poem written during WW1, I bring the poem “The Man He Killed”, by Thomas Hardy that illustrates all these aspects of the war, especially the idea of death.

The Man He Killed – Thomas Hardy (1840-1928)[6]

Had he and I but met

By some old ancient inn,

We should have sat down to wet

Right many a nipper kin!

But ranged as infantry,

And staring face to face,

I shot at him as he at me,

And killed him in his place.

I shot him dead because –

Because he was my foe,

Just so: my foe of course he was.

That’s clear enough; although

He thought he’d ‘list, perhaps,

Off-hand-like – just as I –

Was out of work – had sold his traps –

No other reason why.

Yes, quaint and curious war is!

You shoot a fellow down

You’d treat, if met where any bar is,

Or help to half-a-crown.

Moving toward a different perspective about the events on that Christmas Truce Day, contemporary writes Carol Ann Duffy, Ian McMillan and John F. McCullagh, have written poems that recount those moments, though written a very long time after the first world war, do not only recreate the horrors of war, the misery of being in the front, they also celebrate the peaceful and friendly events that took place on that day and that is what makes our spirit being essentially human.

‘The Game: Christmas Day, 1914’ by Ian McMillan, ‘The Christmas Truce’ by Carol Ann Duffy and ‘The Christmas Truce,1914’ by John F. McCullagh are the poems selected as they capture the humane moment in a war and raise the issue of some people having the misfortune of being there.

The main aspect of this article is to bring some light on the “game” that alleged took place on that Christmas day. The three poems manage to show how important it is to feel human and be humane towards the other while describing the game in different ways. Chants, exchanging of gifts, sharing family stories can also be read in the poems, and the stories told before in this article may be read in full at the end of the article.

As it can be seen in the extracts of some stanzas from the poems, the idea of a ball flying in the air or being kicked somehow in a sort of football match is present in all of them. Nevertheless, it is important to remember that these poems were written about one hundred years after the war and elicit different kinds of individual and collective memories that could have been gathered throughout the years.

The Game: Christmas Day, 1914

(by Ian McMillan)

A ball flies in the air like a moon

Kicked through the morning mist.

All these boys want to have today

Is a generous amount of extra time.

No strict formations here, this morning;

No 4-4-2 or 4-5-1

No rules, really. Just a kickabout

With nothing to be won

No white penalty spot, this morning,

The players are all unknown.

The Christmas Truce

(by Carol Ann Duffy)

Tickler’s jam … for cognac, sausages, cigars,

beer, sauerkraut;

or chase six hares, who jumped

from a cabbage-patch, or find a ball

and make of a battleground a football pitch.

The Christmas Truce,1914

(by John F. McCullagh, 2017)

I hear in some sectors games were played.

a game of football of a sort.

Sadly, it was the briefest pause

ere we resumed our deadly sport.

As it can be perceived in all three poems, the theme of war, the transition that is depicted from a cold, sad, unknown feeling of one who is always ready on his toes for battle, surrendering to a misguided feeling of uncertainness, though being able to being human again. The football match portrayed does not fix the stupidity of the war, however, it helps, at least for a short moment in history, to heal some wounds.

Although these poems create a dissonance with reality or the grand narrative of the war, for a brief moment, the truce and the “game” bring about a life that would be considered almost normal.

Imagine playing football with the troops from the other side but realizing that soon you will have to shoot or be shot, to kill another person who in a different place and moment be your friend rather than your foe. The football match captures the essence of becoming friends, sharing laughter, and sweat, and the idea of having peace after all.

Even though the three authors did not experience the war firsthand, they keep this very eventful incident in memory. These incidents are never going to be forgotten that easily, not by the ones who fought nor the ones who were told the stories. They all try hard to make an honest attempt at trying to capture what the Christmas truce and the match of 1914 felt like in some sort of post memory essence. Essentially, these poems shed some light on the Christmas of 1914 as a reminder that we can always have choices and we can always do something better.

As it was said before, much has been written about World War One, and much of it by soldier poets, which means that war was the main theme of their poetry, not anything else. Maybe, that is one of the reasons why only many years after the war ended, some artwork like poetry and sculptures came about.

Besides, press censorship and military oppression ensured that little information regarding the truces emerged, so that much of the information came directly from soldiers at the front or those wounded in hospitals.

It is important to highlight that the high commands, the ones who did not go to front, put an end on this fraternization between “enemy” lines with court martials, and ordered their men to strike enemy lines.

Many accounts being told by the soldiers can be found describing the area known as “No Man’s Land” as the place where it all happened. Most would say two things: “we had to bury our dead in a part of the war-torn landscape” and as a contrast “this area was temporarily transformed by soldiers who allowed themselves to ‘Make of a battleground, a football pitch’.”

The three poems are written under an anti-war vein, making sense of war, and condemning its atrocities. The whole world would benefit from reading such poems that attempt to bring the ceasefires and fraternizations to life, and this is always welcome.

Another contemporary artwork that was created to celebrate the “game” was the Christmas Truce 1914 Football Remembers memorial at the National Memorial Arboretum, Arlewas, Staffordshire. Erected as a monument to the Christmas Truce football match that was played in the no man’s land of the Western Front between English and German troops during World War I on Christmas Day 1914.[7]

References

Coleman, Julie (2008). A History of Cant and Slang Dictionaries: Oxford University Press.

Websites:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=48650239. Accessed 09 Mar 2022.

https://www.forces-war-records.co.uk/blog/2014/01/30/wilfred-owen-my-subject-is-war-and-the-pity-of-war-the-poetry-is-in-the-pity.Accessed 05 Mar 2022.

https://haventoday.org/blog/silent-night-wwi-christmas-truce/ Accessed 09 Mar 2022

‘Christmas Truce of 1914’. History.com. http://www.history.com/topics/world-war-i/christmas-truce-of-1914. Accessed 10 Jan 2022.

http://www.my-best-books.co.uk/the-christmas-truce-2/ Accessed 17 Dec 2021.

‘The Christmas Truce’. Duffy, Carol Ann. http://noglory.org/index.php/multimedia/poetry-and-spoken-word/35-carol-ann-duffy-the-last-post-2. Accessed 10 Jan 2022.

https://www.poemhunter.com/poem/the-christmas-truce-1914-2/ Accessed 15 Feb 2022

http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/173594. Accessed 30 Jan 2015.

‘The Game: Christmas Day, 1914’. McMillan, Ian. http://poetrysociety.org.uk/poems/the-game-christmas-day-1914/. Accessed 17 Dec 2021.

https://roshanmachayya.medium.com/poetry-and-the-christmas-truce-of-1914827149233b#:~:text=Pope%20Benedict%20XV%20earlier%20in,both%20British%20and%20German%20camps. Accessed 18 Dec 2021.

https://www.rte.ie/centuryireland/index.php/articles/football-match-in-no-mans-land-on-christmas-day. Accessed 09 Mar 2022.

https://www.theguardian.com/profile/carol-ann-duffy Accessed 17 Dec 2021.

‘The Christmas Truce Miracle…’. Brockell, Gillian. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/retropolis/wp/2017/12/24/the-christmas-truce-miracle-soldiers-put-down-their-guns-to-sing-carols-and-drink-wine/. Accessed 10 Jan 2022.

Did The Christmas Truce Football Match Really Happen? History Hit TV. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VIiP3TUFoHw Accessed 17 Dec 2021.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6KHoVBK2EVE&t=12s. Accessed 09 Mar 2022

Poems

The Game: Christmas Day, 1914

(by Ian McMillan)

It is so cold.

The lines of this poem are sinking

Into the unforgiving mud. No clean sheet.

Dawn on a perishing day. The weapons freeze

In the hands of a flat back four.

The moon hangs in the air like a ball

Skied by a shivering keeper.

All these boys want to do today

Is shoot, and defend, and attack.

Light on a half-raised wave. The trench-faces

Lifted till you see their breath.

A ball flies in the air like a moon

Kicked through the morning mist.

All these boys want to have today

Is a generous amount of extra time.

No strict formations here, this morning;

No 4-4-2 or 4-5-1

No rules, really. Just a kickabout

With nothing to be won

Except respect. We all showed pictures,

I learned his baby’s name.

Now clear the lines of this poem

And let’s get on with the game.

No white penalty spot, this morning,

The players are all unknown.

You can see them in the graveyards

In teams of forgotten stone;

The nets are made of tangled wire,

No Man’s Land is the pitch,

A flare floodlights the moments

Between the dugouts and the ditch.

A hundred winters ago sky opened

To the sunshine of the sun

Shining on these teams of players

And the sounds of this innocent game.

All these boys want to hear today

Is the final whistle. Let them walk away.

It has been so cold. The lines

Of these poems will be found, written

In the unforgotten mud like a team sheet.

Remember them. Read them again.

The Christmas Truce

A poem for Armistice Day

Illustration by David Roberts

Carol Ann Duffy

Christmas Eve in the trenches of France,

the guns were quiet.

The dead lay still in No Man’s Land –

Freddie, Franz, Friedrich, Frank . . .

The moon, like a medal, hung in the clear, cold sky.

Silver frost on barbed wire, strange tinsel,

sparkled and winked.

A boy from Stroud stared at a star

to meet his mother’s eyesight there.

An owl swooped on a rat on the glove of a corpse.

In a copse of trees behind the lines,

a lone bird sang.

A soldier-poet noted it down – a robin

holding his winter ground –

then silence spread and touched each man like a hand.

Somebody kissed the gold of his ring;

a few lit pipes;

most, in their greatcoats, huddled,

waiting for sleep.

The liquid mud had hardened at last in the freeze.

But it was Christmas Eve; believe; belief

thrilled the night air,

where glittering rime on unburied sons

treasured their stiff hair.

The sharp, clean, midwinter smell held memory.

On watch, a rifleman scoured the terrain –

no sign of life,

no shadows, shots from snipers,

nowt to note or report.

The frozen, foreign fields were acres of pain.

Then flickering flames from the other side

danced in his eyes,

as Christmas Trees in their dozens shone,

candlelit on the parapets,

and they started to sing, all down the German lines.

Men who would drown in mud, be gassed, or shot,

or vaporised

by falling shells, or live to tell,

heard for the first time then –

Stille Nacht. Heilige Nacht. Alles schläft, einsam wacht …

Cariad, the song was a sudden bridge

from man to man;

a gift to the heart from home,

or childhood, some place shared …

When it was done, the British soldiers cheered.

A Scotsman started to bawl The First Noel

and all joined in,

till the Germans stood, seeing

across the divide,

the sprawled, mute shapes of those who had died.

All night, along the Western Front, they sang,

the enemies –

carols, hymns, folk songs, anthems,

in German, English, French;

each battalion choired in its grim trench.

So Christmas dawned, wrapped in mist,

to open itself

and offer the day like a gift

for Harry, Hugo, Hermann, Henry, Heinz …

with whistles, waves, cheers, shouts, laughs.

Frohe Weinachten, Tommy! Merry Christmas, Fritz!

A young Berliner,

brandishing schnapps,

was the first from his ditch to climb.

A Shropshire lad ran at him like a rhyme.

Then it was up and over, every man,

to shake the hand

of a foe as a friend,

or slap his back like a brother would;

exchanging gifts of biscuits, tea, Maconochie’s stew,

Tickler’s jam … for cognac, sausages, cigars,

beer, sauerkraut;

or chase six hares, who jumped

from a cabbage-patch, or find a ball

and make of a battleground a football pitch.

I showed him a picture of my wife.

Ich zeigte ihm

ein Foto meiner Frau.

Sie sei schön, sagte er.

He thought her beautiful, he said.

They buried the dead then, hacked spades

into hard earth

again and again, till a score of men

were at rest, identified, blessed.

Der Herr ist mein Hirt … my shepherd, I shall not want.

And all that marvellous, festive day and night,

they came and went,

the officers, the rank and file,

their fallen comrades side by side

beneath the makeshift crosses of midwinter graves …

… beneath the shivering, shy stars

and the pinned moon

and the yawn of History;

the high, bright bullets

which each man later only aimed at the sky.

The Christmas Truce,1914

John F. McCullagh, 2017

In the dark, past no man’s land,

When the cold night’s wind whispered low,

We heard a most incongruous sound.

Christmas carols sung by our foe.

Someone raised a flag of truce

and we met them on contested ground.

We shared our food, some cigarettes.

And hummed along with their joyful sound.

Our fellows sang what tunes we knew-

In broken English they replied.

Together we buried our common dead

Who belonged now not to either side.

I hear in some sectors games were played.

a game of football of a sort.

Sadly, it was the briefest pause

ere we resumed our deadly sport.

In years that followed no quarter was given

So bitter had our men become.

There were no songs left in our hearts.

after the slaughter of Verdun.

Notas

[1] In World War I and other wars that involved trench warfare, the term “no man’s land” denoted the space between the trenches of two or more belligerent forces. This territory was not controlled by either side, it was a neutral place on the battlefield. “No man’s land” was a very dangerous area because it didn’t provide any of the cover that trenches did. However, soldiers were forced to cross it as they advanced, and those responsible for evacuating the wounded had to cross it to transport soldiers for treatment. Inevitably, they would end up dead trying to fetch the wounded and the corpses of their fellow soldiers. The WW1 was the most famous trenches war as it can be depicted in history books. There would be no gain in territory for months, barely inches, and the trenches would also be differently built as the British were more rudimentary whilst the German more refined.

[2] https://www.rte.ie/centuryireland/index.php/articles/football-match-in-no-mans-land-on-christmas-day. Accessed 09 Mar 2022.

[3] https://haventoday.org/blog/silent-night-wwi-christmas-truce/ Accessed 09 Mar 2022

[4] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6KHoVBK2EVE&t=12s Accessed 09 Mac 2022

[5] https://www.forces-war-records.co.uk/blog/2014/01/30/wilfred-owen-my-subject-is-war-and-the-pity-of-war-the-poetry-is-in-the-pity Accessed 05 Mar 2022.

[6] http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/173594. Accessed 30 Jan 2015.

[7] https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=48650239 Accessed 09 Mar 2022.